The other day, around 3:45 p.m., my wife started watching the Harry Potter movies on TV. As soon as the theme song wafted into my ears from the other room, I was done for the day. What am I supposed to do, not watch them?

But it also got me thinking about language, and the Harry Potter series in general. I and much of my generation grew up with Harry, literally - I read the first book when I was 12 and the last when I was 19. I remember getting the 7th book at midnight and pulling an all-nighter to read it before my lifeguarding shift that the next morning. I know J.K. Rowling is busy espousing some Very Bad and Problematic opinions these days. I also realize that the idea of “Death of the Author” is kind of impossible to fully embrace.

But if we can disassemble just part of that for a bit of analysis,

How is it that these books were equally impactful to a 12-year-old and a 19-year old? Those are a big 7 years, with a lot of learning and changing and growing. How did that series grow and change with us? We should find out. We have the tools.

exploratory analysis music plays

It’s time for some exploratory analysis!

Let’s dive in

Specifically, what we’re looking for here is how, if at all, does the text of HP books change between Book 1 and Book 7? Can we measure either a change in tone or complexity?

The first thing we need to do is load our data. Thankfully, the text of the Harry Potter Series can be found on archive.org. I went ahead and downloaded the txt. files.

First, complexity

How can we try to assess complexity of a piece of writing? Literary critics and teachers have a lot of thoughts on this exact subject! However, most of that methodology revolves around combing qualitative and quantitative methods as well as expert assessments of the literary texts in question. Unfortunately, we really only have quantitative measures to use here.

Never fear, we are doing exploratory analysis! So let’s get in there and try some stuff.

One thing that really informs my process here is my old career as a journalist. Journalism, much like J.K. Rowling, has a lot of problems at the moment – and in general. However, also much like J.K., journalism is really good at making writing accessible. Two specific rules I think help try to grade complexity in text:

The number of words in a paragraph

The level of uncertainty in a specific text

Let’s take a look at each, along with some simple statistical tools to tell us if we’re on the right track.

How many words in a paragraph

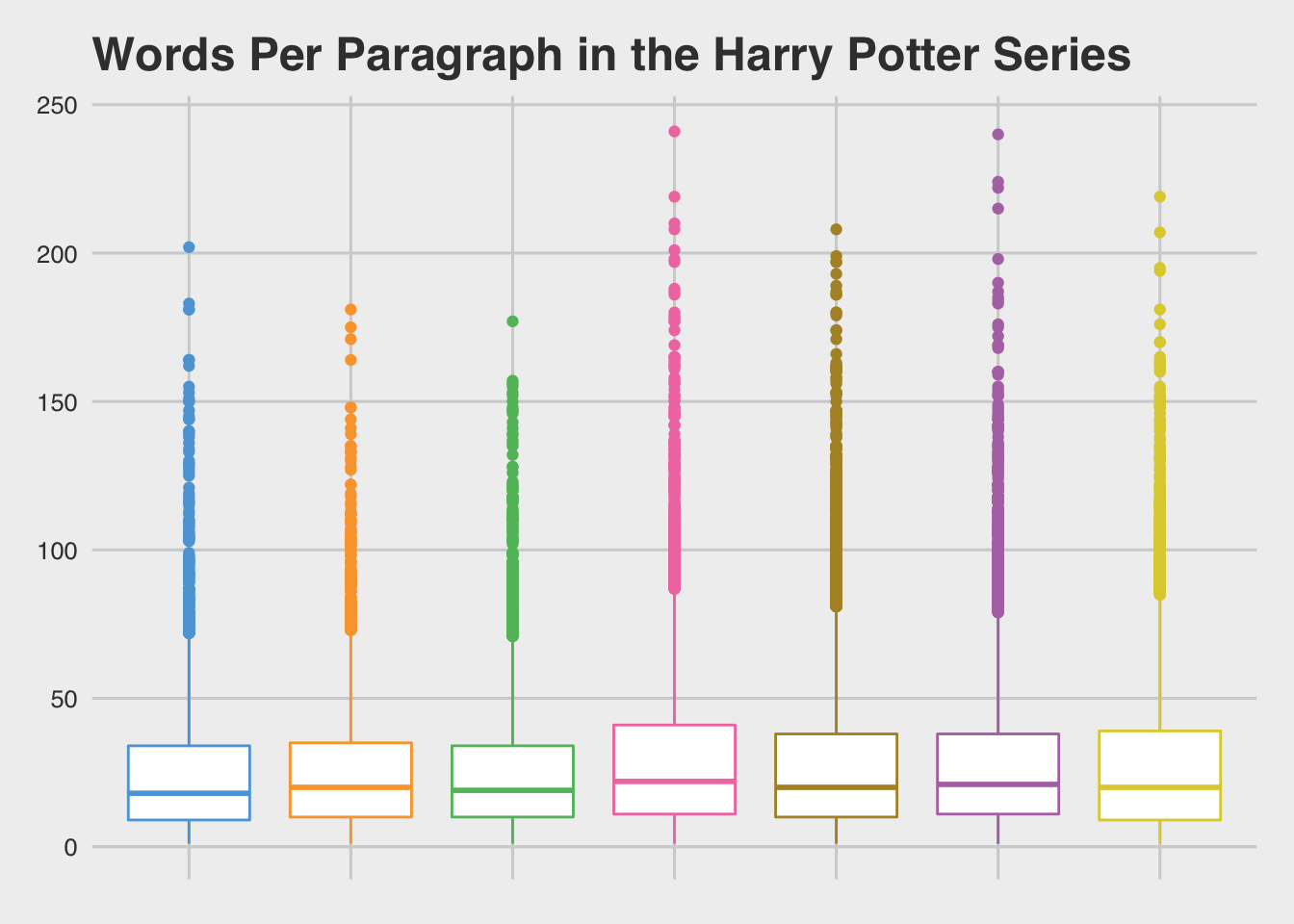

One rule from journalism is that paragraphs should be around 35 words, 50 is on the high end. There are a lot of reasons for this as a good indicator: readers like white space, and don’t like to wade through long, solid blocks of text. Also, longer paragraphs tend to involve more convoluted reasoning or a bunch of complex ideas and clauses. The basic rule of thumb: the more words in a paragraph, the more complex the paragraph.

Just eyeballing the distribution, there seems to be some small differences between the length of the paragraphs, though it’s largely in the long tail of outlier paragraphs (that’s all the dots outside of the boxes). When we take some summary stats, we see a similar story: the long tail of longer paragraphs is dragging up the average, while the median remains fairly steady.

Let’s run a quick-and-dirty analysis of variance to see if these differences really are similar.

What we’re going to do here is run an anova (or analysis of variance) to try to see how much real difference there is between these groups, and how much of that difference can be explained by the factor we choose.

We’re going to layer into that a Tukey HSD (which stands for Honestly Significant Difference, because John Tukey is awesome). The Tukey HSD gives us visibility to just how difference each LEVEL of the factor is from every other level. So, is book one different from book two? what about book three? And so on and so forth. This is how we’re going to take these big, ungainly distributions and sort out the true differences.

library(stats)

variance <- aov(words_in_graph ~ doc_id, data = paragraphs )

summary(variance)

## Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F)

## doc_id 6 113363 18894 28.02 <2e-16 ***

## Residuals 38830 26179896 674

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

TukeyHSD(variance)

## Tukey multiple comparisons of means

## 95% family-wise confidence level

##

## Fit: aov(formula = words_in_graph ~ doc_id, data = paragraphs)

##

## $doc_id

## diff lwr upr p adj

## book2-book1 0.60750667 -1.3222676 2.5372809 0.9681402

## book3-book1 -0.41089632 -2.2282010 1.4064084 0.9943486

## book4-book1 5.05833529 3.3644417 6.7522289 0.0000000

## book5-book1 2.69105707 1.0862873 4.2958268 0.0000158

## book6-book1 3.43774811 1.7247643 5.1507319 0.0000001

## book7-book1 2.64069022 0.9778151 4.3035654 0.0000582

## book3-book2 -1.01840299 -2.7966043 0.7597984 0.6237817

## book4-book2 4.45082862 2.7989572 6.1027001 0.0000000

## book5-book2 2.08355040 0.5232012 3.6438997 0.0016023

## book6-book2 2.83024145 1.1587998 4.5016831 0.0000124

## book7-book2 2.03318356 0.4131350 3.6532322 0.0040516

## book4-book3 5.46923161 3.9502692 6.9881940 0.0000000

## book5-book3 3.10195339 1.6830604 4.5208464 0.0000000

## book6-book3 3.84864443 2.3084221 5.3888668 0.0000000

## book7-book3 3.05158654 1.5672938 4.5358793 0.0000000

## book5-book4 -2.36727822 -3.6242335 -1.1103229 0.0000006

## book6-book4 -1.62058718 -3.0130541 -0.2281203 0.0107555

## book7-book4 -2.41764507 -3.7479850 -1.0873052 0.0000018

## book6-book5 0.74669105 -0.5358746 2.0292567 0.6049166

## book7-book5 -0.05036684 -1.2651980 1.1644643 0.9999997

## book7-book6 -0.79705789 -2.1516214 0.5575056 0.5924270Yeah, the analysis of variance comes back with an itty-bitty p-score, meaning there are some significant differences between the paragraph lengths in different books. A TukeyHSD analysis, likewise, points us to the idea that SOME books are very similar, while others are really different. It seems as though, roughly, books 1-3 are written at one level of complexity, while books 4-7 at a different, higher one.

Number of questions

Another rule from Journalism is the Six W’s, or the Five W’s and how (I just call it Six W’s).

The premise here being in order to have a coherent narrative, you should be able to answer the following questions:

Who

What

When

Where

Why

How

The first four are the easy ones: John Dorian robbed the first street bank on Thursday morning.

The last two, well those are the more esoteric and tricky stuff. Why did John Dorian rob that bank? Ad how did he get away? Well….. (Another rule of thumb: if your question elicits a ‘well…’ as part of the answer, it’s probably a hard question)

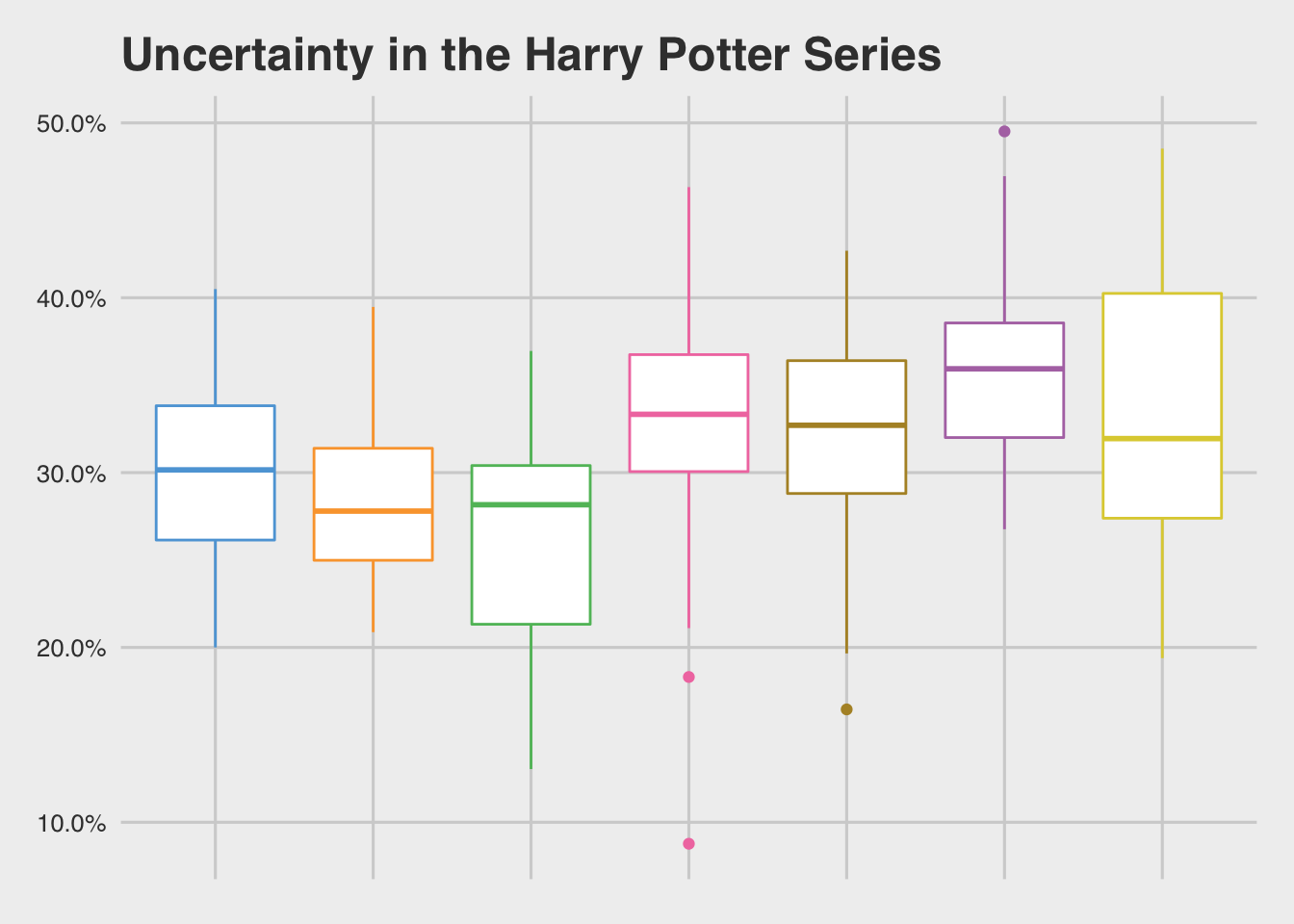

Basically, questions add complexity. Why and How, specifically, add additional depth and complexity. What if we were to count the ratio of paragraphs with questions, with a special weight to how and why?

We’ll do our same analysis again: an anova analysis with a Tukey HSD. But just from the graph above, we’ll probably see a noisier but similar finding: later books are more complex than earlier books.

why_aov <- aov(uncert_index~doc_id, data=whys)

summary(why_aov)

## Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F)

## doc_id 6 0.1456 0.024267 5.669 1.94e-05 ***

## Residuals 189 0.8090 0.004281

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

TukeyHSD(why_aov)

## Tukey multiple comparisons of means

## 95% family-wise confidence level

##

## Fit: aov(formula = uncert_index ~ doc_id, data = whys)

##

## $doc_id

## diff lwr upr p adj

## book2-book1 -0.013749274 -0.080748386 0.05324984 0.9963906

## book3-book1 -0.036868012 -0.101575874 0.02783985 0.6181827

## book4-book1 0.030123431 -0.028221470 0.08846833 0.7210503

## book5-book1 0.026608414 -0.031504268 0.08472110 0.8198118

## book6-book1 0.057811676 -0.002553173 0.11817653 0.0702681

## book7-book1 0.028276486 -0.030312537 0.08686551 0.7802523

## book3-book2 -0.023118738 -0.085753038 0.03951556 0.9274544

## book4-book2 0.043872706 -0.012163673 0.09990908 0.2337274

## book5-book2 0.040357688 -0.015436863 0.09615224 0.3248069

## book6-book2 0.071560951 0.013424359 0.12969754 0.0057757

## book7-book2 0.042025761 -0.014264752 0.09831627 0.2871341

## book4-book3 0.066991444 0.013715725 0.12026716 0.0043736

## book5-book3 0.063476426 0.010455125 0.11649773 0.0081543

## book6-book3 0.094679689 0.039199154 0.15016022 0.0000180

## book7-book3 0.065144499 0.011601541 0.11868746 0.0066885

## book5-book4 -0.003515017 -0.048551431 0.04152140 0.9999865

## book6-book4 0.027688245 -0.020219060 0.07559555 0.6018544

## book7-book4 -0.001846945 -0.047496352 0.04380246 0.9999997

## book6-book5 0.031203262 -0.016420956 0.07882748 0.4483740

## book7-book5 0.001668072 -0.043684157 0.04702030 0.9999998

## book7-book6 -0.029535190 -0.077739505 0.01866913 0.5321773And sure enough, later books are more complex. Particularly, Books 4-7 seem to have more layers of complexity than Books 1-3. That’s super interesting!

Complexity Verdict: between ‘maybe’ and ’probably

By both of our somewhat arbitrary measures, complexity seems to increase at least marginally as the series progresses. The text is definitely more dense, but there are a lot of other analyses that might give us more detailed information.

You could get deeper here in a lot of ways, but in this case, we’re just trying to poke around and see what we can see a little bit.

Sentiment and tone

As we are dealing with weightier stuff, if the language changes, does the tone then also change? not necessarily, as writers like David Sedaris and Douglas Adams can prove.

But how are we supposed to judge ‘tone’? Good news, we’ve got a bunch of lexicons for judging tone and sentiment.

Language processing is tricky. I can write something as sarcasm and you can read it as sarcasm, but computers really have trouble parsing out implicit and explicit meaning. Turns out human communication is a miracle.

But what we do have is a huge range of libraries that classify some words that are almost always explicitly good or bad. We can use those in R as well, specifically through the textdata and tidytext packages.

We’ll load the “afinn” lexicon, which is a numeric scale from -5 at the most negative to 5 at the most positive,

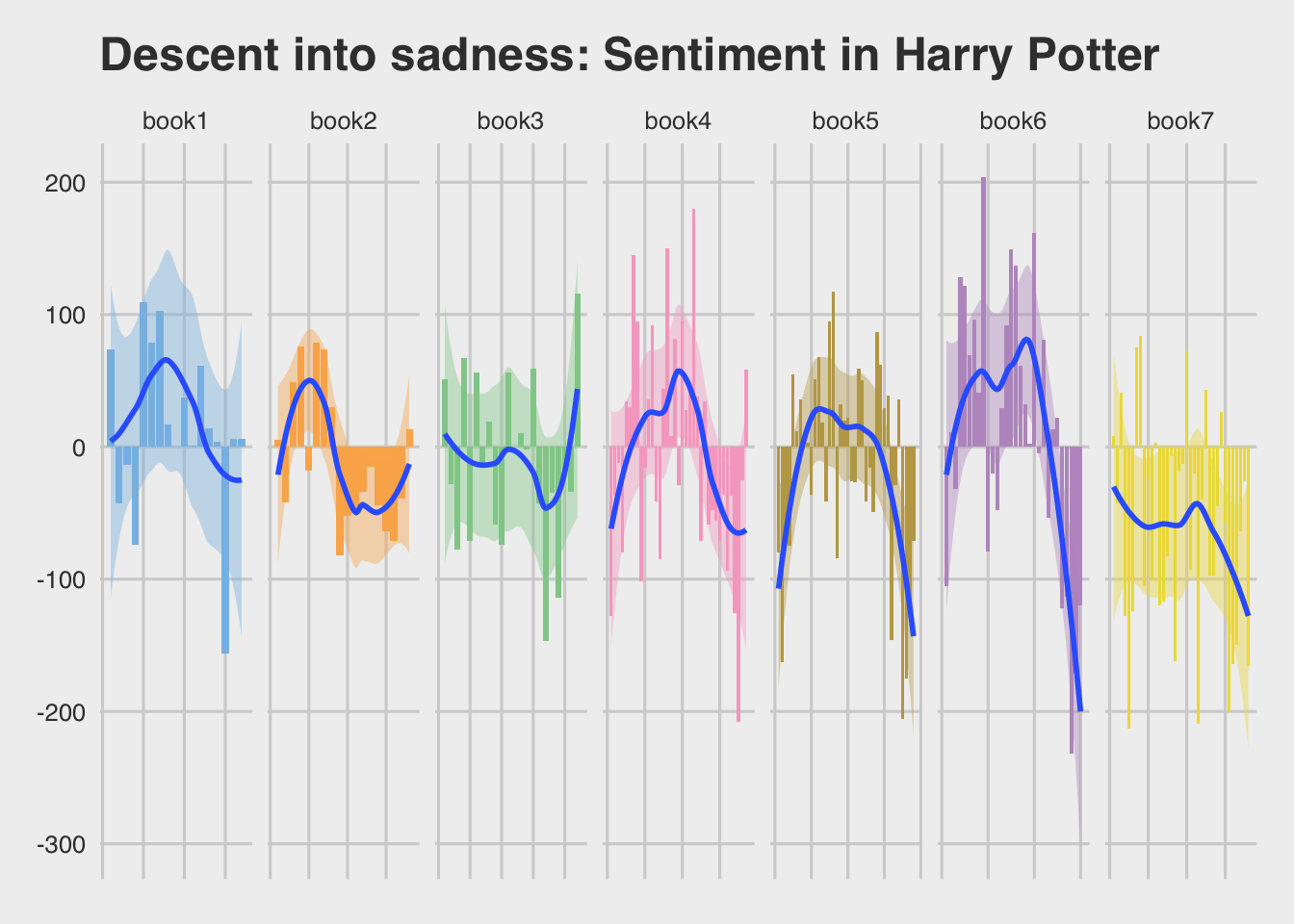

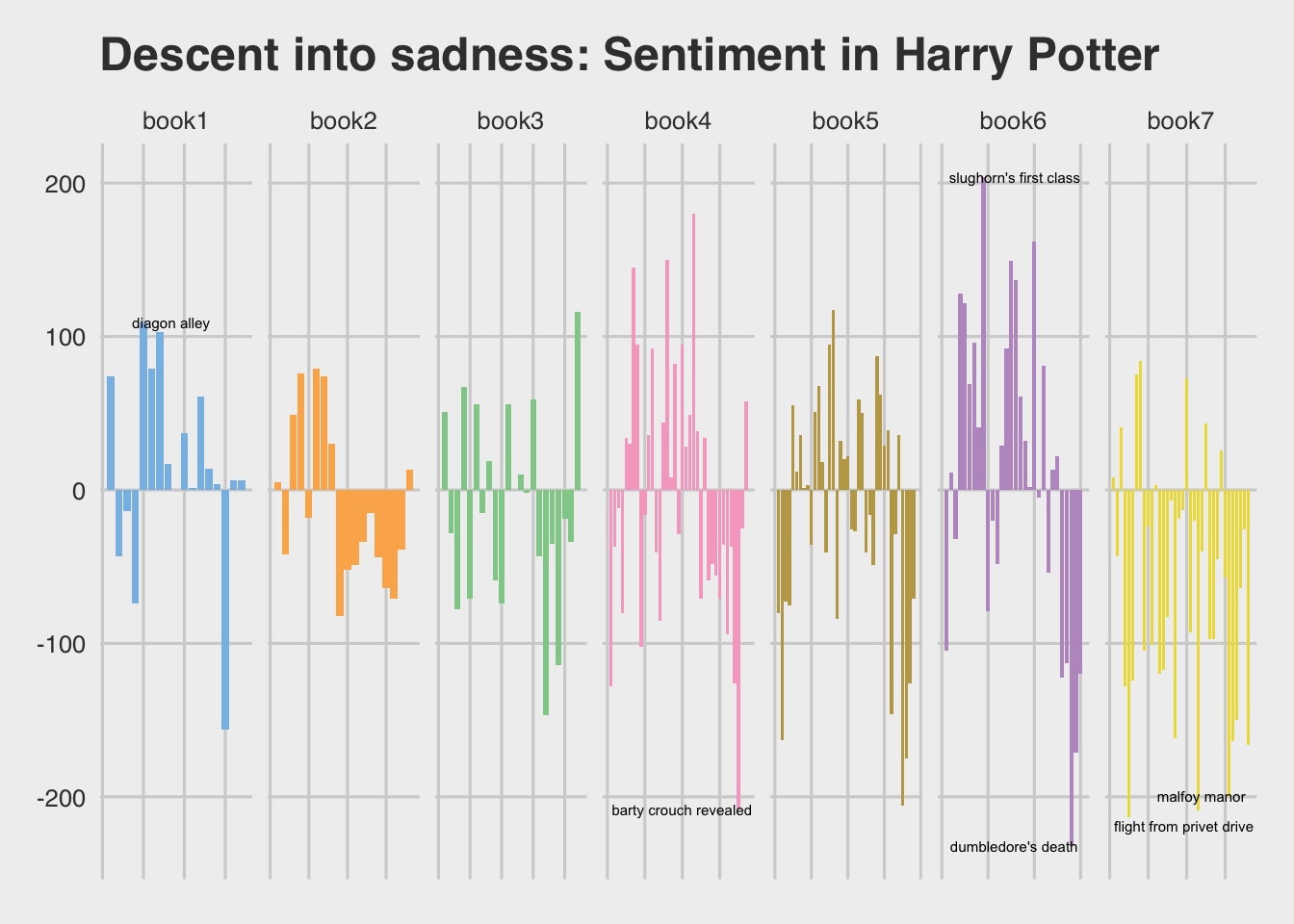

So what happens when we plug the Harry Potter Books into these metrics and see what we get?

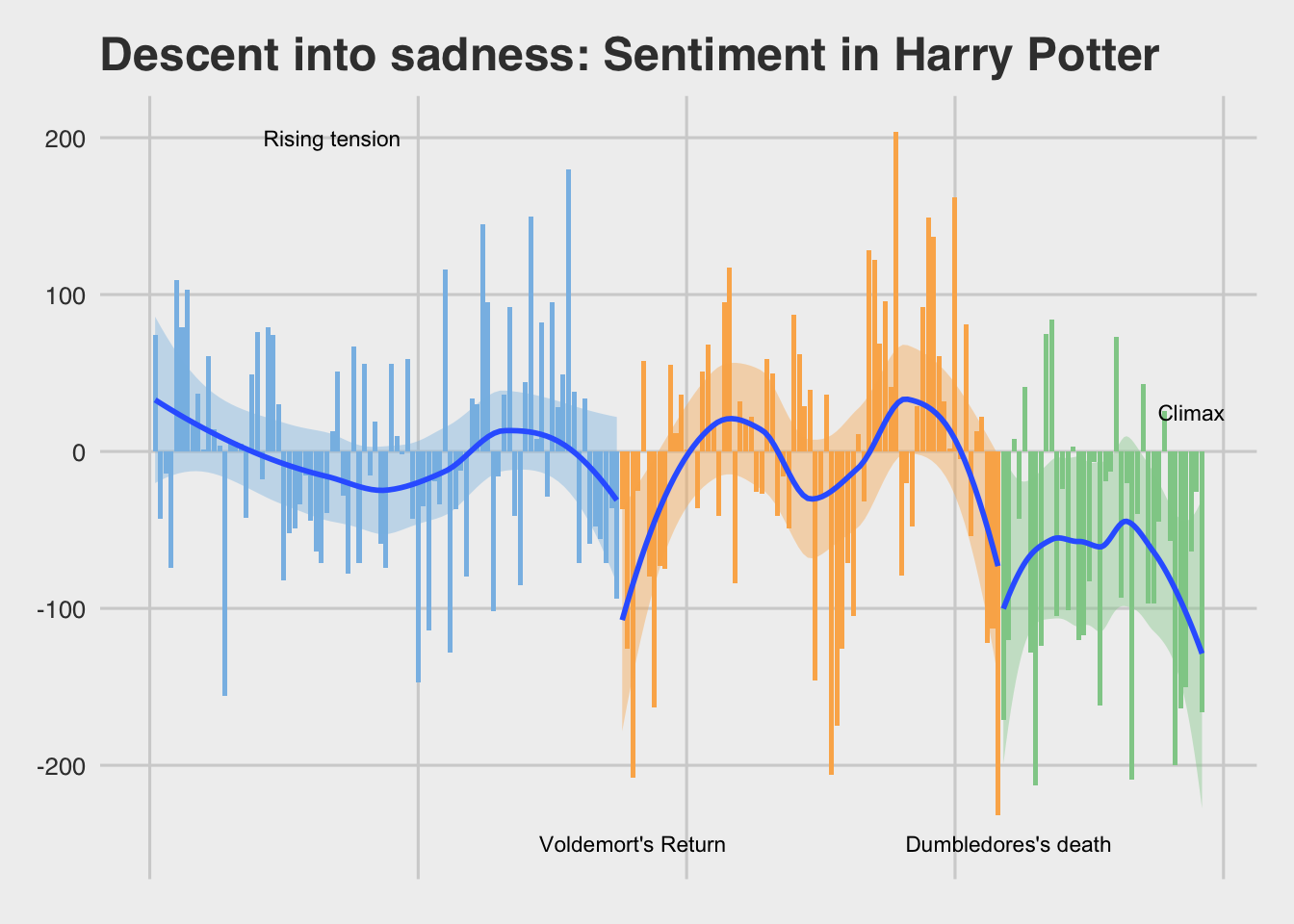

Shew, buddy. Things get DARK in the last half of this series. Tonally, once He-who-must-not-be-named returns, the series gets grim in a hurry. Which, you know, makes sense! Ethno-nationalist, genocidal maniacs taking over is bad! Stares blankly in 2020

But is there something deeper lurking here?

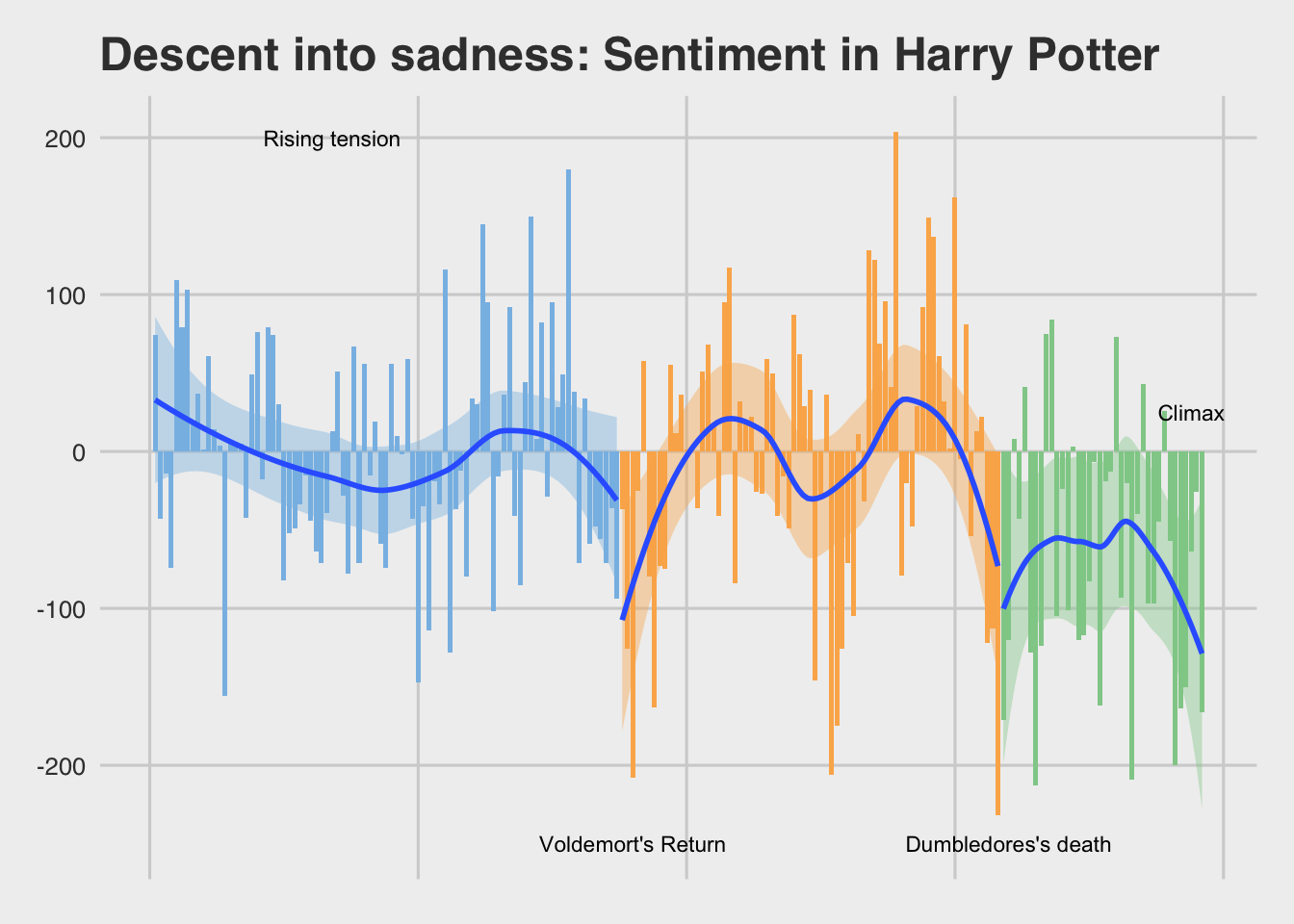

These books are a continuous narrative. Should we simply look at these books as one as well?

If you look at the books as a continuous whole, it hews really tightly to three-act structure. We’ve got midpoints, rising action, even really nice act breaks.

What can we say about all this?

Now that we have done all our analysis, what can we feasibly say about how the text of Harry Potter changes and grows with its readers, if at all?

- Later books have deeper and more extended valleys of negative sentiment, usually when the book is processing some traumatic event: Dumbledore’s death and Sirius Black’s death are good examples of this, not to mention Harry’s own ruminations as he walks into the forest.

- As the texts themselves lengthen, Rowling seems to have lengthened her paragraphs, trusting readers to follow both longer descriptions as well as more nuanced and layered mysteries in the later books.

Does this align with our own progression from tween to young adult? One hypothesis could be that we simply wish even our fantasy worlds to reflect our maturing sensibilities about the world - and the inherent darkness we encounter as part of growing up. Another hypothesis could be that we need higher and more real stakes to keep the story moving forward and holding our attention.

Or, it could be that Rowling improved as a writer and delved deeper into the world she had created, fleshing it out and polishing it just as we improved as readers and sought out deeper topics and weightier things. Maybe we, as readers, were just ready for the discussion of mortality and sacrifice, and for the natural progression of a story in which we were already invested.

Packages used to create this:

tidytext|text2vec|readtext|scales|ggthemes|stats|ggrepel|tidyverse|quanteda|lintr

Twitter

Google+

Facebook

Reddit

LinkedIn

StumbleUpon

Pinterest

Email